by Charlotte Gleeson, Manchester Enterprise Academy

Research question

To what extent do paired discussion activities, implemented for half a term, improve confidence in oral responses among high ability working class girls?

Project Rationale

The school that I work at serves a community in the top one percent of social deprivation across the country; our Pupil Premium (PP) figures average around seventy percent compared to the national average of twenty five percent. Consequently, I chose to focus on how developing oracy impacts on progress for PP students.

Currently, the academy is focusing on progress for white PP boys, a group who are underperforming comparatively to their peers and initially this seemed a great starting point for my research project. However, after teaching a presentation based lesson to my top set year nine group, I was pushed in another direction when all of my PP girls refused to get up and present.

After discussing the reasons behind this, it became clear that although they were high academic achievers, they also felt worried about sharing their ideas in front of a group. I began to track who was volunteering answers in class and it became clear that as well as refusing to present in lesson, these girls were also rarely putting their hands up in class to answer questions or contributing to discussion.

Despite outperforming the boys in written assessments, girls were being passive in the oracy aspect of my lessons.

In Loud on the Inside: Working- Class Girls, Gender and Literacy (2006), Pamela Hartman suggests that “even though girls may be doing better than boys in some respects, girls have qualitatively different experiences”. She argues that girls receive less teacher attention as they tend to engage less in discussion and questioning.

The idea of quiet, well-behaved girls falling through the gaps was something I could recognise in my own practice. It was imperative that I encouraged the girls to make more oral contributions so that I could make a better assessment of their learning, probe them to think further, and help them to develop their oracy skills.

Baseline data

I chose the girls for the study by recording how many times all students answered a question in class using a tally system on a printed seating plan. I then worked out the average number of questions they volunteered per lesson over a series of ten lessons leading up to the study. The results can be seen in Table 1, below. There were six female PP pupils chosen because, on average, they volunteered less than one answer a lesson.

This idea was reinforced by survey data which showed that more than 67% of students chosen for the project disagreed with the statement: “I feel confident about sharing my ideas in front of the whole class.”

To pick this apart further, I conducted interviews with a range of pupils. One girl said: “I don’t like getting involved in case I get it wrong and I look stupid in front of you and the rest of the class.” Interestingly, she said that the pressure wasn’t as intense in small groups. This was also reflected in the survey results which showed that 83% agreed with the statement: “I feel confident about sharing my ideas in a small group.”

In The State of Speaking in Schools report (2016), Millard and Menzies recommend using paired work to “help reduce pupil’s social anxiety around public speaking”. They write that small group work can “help build confidence and give pupils the time to consider their response before answering a question [which] can increase the depth of verbal dialogue in lessons.” For this reason, I decided to make paired work an integral part of my study.

Intervention & Impact

I planned a series of fifteen lessons which would each have an element of group/paired discussion, starting with a quiz where I would track voluntary contributions from students. The intended impact was that through practising with their peers in small groups, the six female students would become more confident in sharing voluntary responses in front of the whole class.

To tackle the anxiety students felt surrounding incorrect answers, I endeavoured to create a “safe space” for discussion. I shared and referred back to Voice 21’s “guidelines for talk” and “expectation of listening” which emphasises respecting other people’s views and models to pupils how to show good listening skills.

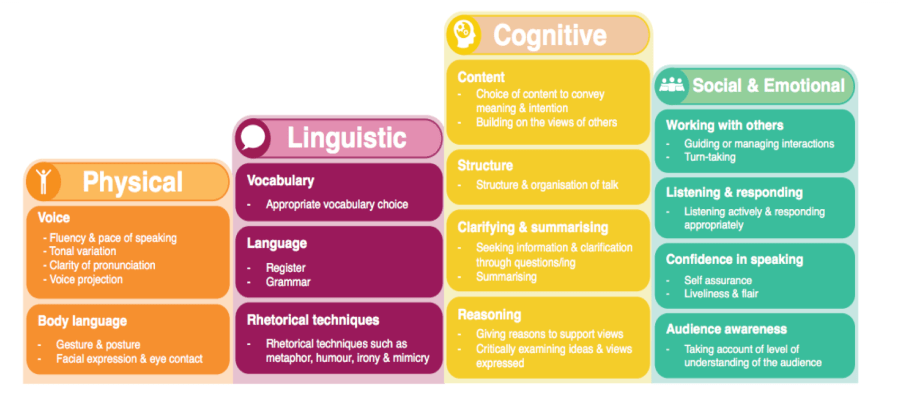

In addition, I scaffolded paired conversations by giving pupils sentence stems and key vocabulary to help start or guide their interactions. Secondly, I used “talk detectives” where a small group of students go around the room listening to conversations and note down positives and targets for the class according to the four strands of the Oracy Skills Framework (see below). This was intended to again create a “safe space” as classmates specifically praised each other for elements of their discussion.

Impact data

I collected both qualitative and quantitative data from the project, combining surveys and interviews. The data revealed that on the whole the project achieved some success in encouraging the six female pupils to engage more with oracy in lessons. For example, two of the six students saw their voluntary answer average double during the intervention period.

In a second survey taken after the intervention, 80% of pupils agreed with the statement “I feel more confident putting my hand up after doing group work”. Similarly, in a second set of interviews I asked pupils: “How do you feel about getting involved with discussion now that this half term is over?” One student replied: “I feel better because I know what to expect now. Before I was scared of how people were going to respond, but now it’s become a part of our routine and I feel comfortable.”

From my perspective, I am convinced that focusing on making scaffolded group work a more consistent component of my practice has improved my students’ confidence in oracy. However, the key to success has been making sure it’s well structured, well modelled, and monitored. Without this, the group work can become unfocussed, or dominated by one pupil. Using the sentence starters and talk detectives helped with this (see Figure 1).

There is still work to do in terms of creating the safe space where discussion can flourish. Early on in the intervention, wrong answers were still met by occasional sniggers which I had to correct by reinforcing the guidelines for talk and listening. The damage this can do to students’ self-esteem can be lasting and this is reflected in the fact that 40% of pupils disagreed with the statement; “My classroom is a safe space where I won’t get laughed at”. This shows that there is still potential for anxiety around sharing oral answers.

In the post-intervention interview, pupil 1 said that she would “feel nervous about working in groups with new people in class” as she “doesn’t know them as well” as her last group. Rotating groups more frequently needs to be the next step in increasing confidence in pupils as well as continually reinforcing expectations for respectful listening and what this looks like.

Research ethics

Initially, I did not want the students to know that I was conducting research. I was concerned that if students knew I was analysing them then their behaviour would change. However, after analysing the initial data (the number of volunteered answers per student) I realised that I needed qualitative data to understand why they were not contributing. As soon as the students had taken part in surveys and interviews, it was obvious to them that I was focusing on this aspect of their learning and their behaviour could have altered in response. Next time I conduct research I could ask students broader questions covering more aspects of their learning, so it isn’t as obvious.

However, I don’t think this issue was that damaging to my research project as all it did was highlight to students that I valued their oral contributions in lesson. All this means is that teacher expectations also will have to factor in to why student’s responses improved.

References

Hartman, P. (2006). “Loud on the Inside”: Working-Class Girls, Gender and Literacy. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(1), p.82.

Millard, W. and Menzies, L. (2016). Oracy: The State of Speaking in Our Schools. [online] LKMCO. Available at: https://www.lkmco.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Oracy-Report-Final.pdf [Accessed 30 May 2019].