Rebecca Carter, Silsden Primary School

Project rationale

Over a number of years in teaching, I have observed a lack of articulacy amongst low attainers. Unable to express themselves because of a lack of vocabulary and poor grammar, these children are often the ones to struggle at school and become disaffected, leading to behavioural issues. In his book Closing the Vocabulary Gap (2018), Alex Quigley explains that without exposure to a broad vocabulary from an early age, children are at a distinct disadvantage from which there is little social mobility.

With this in mind, it seems obvious that enabling students to develop a broad vocabulary that becomes embedded in their speech should have a positive effect on their ability to communicate, both verbally and in writing. This led to my research question which was:

To what extent does verbal rehearsing, implemented for three months, improve the quality of writing, especially vocabulary use, among low attaining pupils?

The group I chose to observe were among the low attainers in my class of twenty-seven Year 6 students. I deliberately excluded those with Special Educational Needs (SEN), since the nature of their needs is often wide-ranging. Instead, I chose to examine closely those children whose literacy skills were clearly limited, and whose progress at school to date has consistently fallen below age-related expectations.

Baseline data

Using the school’s progress tracker, it was easy to identify the students who had consistently been cited as those who were classed as ‘commencing’ age-related expectations in the final assessments of the year. However, this data enabled me only to select the pupils for my research project. A more useful measure was to compare the range of vocabulary used by the high and low attainers and to see if the gap could be closed. I closely examined the range of different words used by three high and three low achievers and compared them. As a crude measure, the difference in word choice variety was approximately 50 words. This data suggest that the higher ability children had approximately 25% more words at their disposal than the lower attainers.

Intervention & intended impact

To attempt to close the vocabulary gap, I combined a variety of strategies in my classroom. The first change was simply to elevate the profile of talk, and to persuade the students that by talking they were still learning. The pupils had little aversion to talk, but tended to see it purely as a social activity rather than a medium through which to acquire knowledge or to progress their understanding.

Using a variety of discussion roles, students became aware of the different responsibilities involved in discussion. Some students naturally gravitated towards particular roles, whilst others took them on more reluctantly. It was clear that the low attainers preferred ‘challenging’ or ‘building’ to ‘probing’ or ‘summarising’, as the former two roles require less original thought. In addition, using the Harkness method and recording contributions on conversation flow charts enabled the students to recognise their speech patterns, and also to become aware of those pupils who needed to be encouraged to engage more in talk activities.

Finally, using talk tokens, limiting children in a whole class discussion to just three contributions, made the children think before speaking and had the effect of making their comments more constructive.

Whilst these approaches tackled class talk and had a positive effect in terms of verbal contributions and the enhancement of listening skills, to improve the writing of low attainers the talk had to be translated into work on the page.

Three main strategies were developed:

Use of target vocabulary. Through discussion, students were encouraged to find a wide variety of words and synonyms for a particular topic and then to grade them on a simple target board into good/ better/best. Using talk, dictionaries and thesaurus, a broad range of vocabulary was developed. Students were able to combine the words into useful phrases for their writing and enjoyed experimenting with them. Using verbal rehearsing, the students would first try out a sentence on a white board before reading it to a partner who could offer feedback. In addition, in lessons, students were encouraged to try a sentence using a ‘good’ word to be superseded by a ‘better’ and finally a word from the ‘best’ category.

Use of explicit sentence stems. Students identified in their writing a reliance on sentences which started with determiners or pronouns. Playing an oracy ‘game’ where they were required to begin their sentence with different sentence stems – eg, start with a conjunction /adverb /adjective /preposition.

Peer reading. A very useful strategy whereby a student’s writing is read aloud to them by their partner who becomes their critical friend. This has fantastic effects as the partner is able to spot errors that the writer has overlooked and also is able to question their understanding of the work.

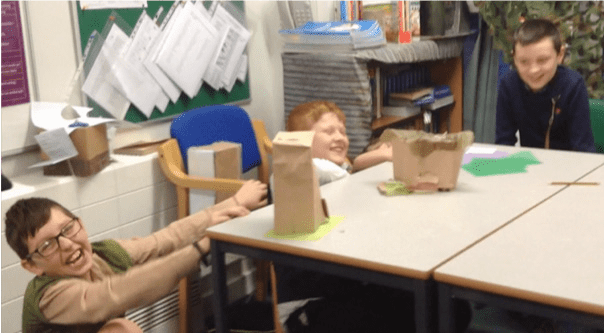

Image shows a verbally written and rehearsed play:

Impact data

Data collected was both quantitative and qualitative. Comparing first the writing assessment data from across the three classes in Year 6, the figures suggest that the impact of oracy on the classes has been considerable, with the highest percentage of pupils expected to achieve age-related expectations being in the base class.

Whilst this is encouraging, it is obvious that the main problem with research of this type, is that it does not address all of the writing criteria expected in the KS2 final assessments. For example, the issues of consistently joined handwriting, spelling and the use of a full range of punctuation are just a few additional factors that can obstruct attainment at Key Stage 2. More compelling data came in the form of a questionnaire conducted in the base class.

Students were asked about their enjoyment of writing and the sources that they have used to inspire it. Overwhelmingly, they cited: idea sharing; trying out ideas with my partner; having someone to talk to about my work; magpie-ing ideas from other people; writing conferences; using the target vocabulary board; hearing other people’s ideas. These responses can be seen in the survey data (Appendix 1).

Although it is a fairly crude measure, the comparison of vocabulary range was repeated after the oracy intervention. At the beginning of the project the results suggested a 25% difference between high and low attainers; by the end of the project, this had reduced to around 15%.

Research Ethics

Having three classes in our current Year 6 cohort presented a useful opportunity for comparison. The other class teachers were fully appraised of what I was doing and were happy to supply their data. Obviously there will always be issues when having to look across a year group to monitor progress but we are also aware that there are other factors which can affect progress. With our writing outcomes being moderated this year the concerns may be heightened.

Evaluation

By the time that students are in year 6, they are aware of their position within in a class in terms of ability. Talk, however well introduced and scaffolded, is immediately exposing as it reveals instantly a level of cognition. Whilst the low attainers have undoubtedly benefitted from developing their understanding of oracy, it is clear that it would be of greater benefit to all stakeholders if the strategies were introduced at the beginning of their educational journeys.

The next steps are clear:

- Introduce pupils to high quality talk experiences and strategies from EYFS

- Encourage all teaching staff to adopt talk protocols and to use them until they are firmly embedded in whole school practice.

- Continue to elevate the importance of talk across school using talk assemblies, pupil-led parents’ evenings, pupil-display days and ‘speech’ days.

Appendix