Richard Sternberg | Byron Court Primary School

Project rationale

I am interested in how teachers can positively influence character, well-being and personality. As Mental Health is a topic receiving intense scrutiny in education currently, I set out to explore how developing oracy skills can affect social and emotional well-being. My initial research revealed several key points which greatly appealed to me:

- Speech is a central factor in the development of personality and closely related to human happiness (Wilkinson, 1965)

- Specific oracy skills need to be taught (Hewitt and Inghilleri, 1993)

- Students’ oral language skills directly relate to their reading and writing academic achievement (Dockell and Connelly, 2009)

- Employers regularly complain that applicant’s oral communication skills are in decline (Alexander, 2013)

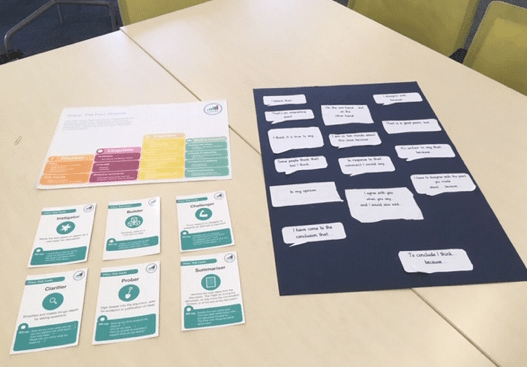

The above summaries made me aware how oracy skills directly influence life-chances, personality and happiness, and how crucial the role of teacher is in developing these skills. I wanted my students to understand the value of oracy skills in everyday contexts, including understanding their own role and the role of others within group talk. This directly lent itself to focusing on Voice 21’s six speaking roles in group discussion (instigator, builder, prober, clarifier, challenger and summariser).

I decided to focus my oracy project on a year 5 intervention group who represent a range of needs (and oracy skills). I also believed the students had the right level of maturity to embrace and use the six speaking roles in group discussion.

Research question:

To what extent does using the six speaking roles, once a week for 12 weeks, improve the number of valuable contributions made by six Year 5 SEND Support students in group discussions?

I defined a ‘valuable contribution’ as either:

- something that clarifies what you are thinking

- moves the group conversation forward

- adheres to the four oracy strands (physical, linguistic, cognitive, social and emotional)

Baseline data

- A whole-school learning walk made it clear how wide-ranging the value was placed on students’ oracy skills, and how inconsistent teacher subject knowledge was including maintaining high expectations (Alexander, 2013).

- Lesson observations of the target students highlighted how some children did lots of talking, but little of it was of value, and other children contributed little but demonstrated they were listening well.

- A group interview discussed ‘speaking and listening’ generally in the classroom, time for group talk, opportunities to speak in lessons and so on. The students talked about how being collaborative and talking to each other helped learning and “helps you think.” They also spoke about respecting others and “giving others a chance to speak.” One student said, “When you’re listening you just sit there and do nothing.” As a group they were interrupting and talking over each other, displaying poor posture and little eye contact. Interestingly, there was only agreement.

- An initial Harkness discussion reinforced the lesson observations: two students spoke too much and only to each other, ignoring the others; two students sat silently, but listening; two kept looking at me to guide them. These characteristics would dominate the first few weeks of the intervention.

Intervention & intended impact

There were a range of personalities and needs in the group. As it was an ‘SEND Support’ group, two students were identified with a Social, Emotional and Mental Health (SEMH) need, two with a Moderate Learning Difficulty (MLD) in literacy or numeracy, and two with an English as an Additional Language (EAL) need.

I had one 30-minute lesson with this target group once a week and chose to split the lesson into the following:

- Five minutes – introducing then re-introducing the six speaking roles (displaying them in front of the group for reference).

- Twenty minutes – one Harkness discussion based on a thought-provoking yet accessible question that I would introduce (‘What traits do you look for in friends?’ ‘If you could have any superpower, what would it be?’)

- Five minutes – share my observations of the group discussion and individual contributions.

My intended impact was to see a progressive increase in the number of quality contributions in a group discussion – comments or questions that were relevant and revealed what the student was thinking, concisely.

Impact data

I recorded the Harkness discussion data for each student as ‘Number of Contributions’ (NC) and ‘Number of Quality Contributions’ (NQC) using a tally chart. I shared this data with the group at the end of the discussion and gave examples of the comments/questions they said. From this the percentage of Quality Contributions can be identified. See below table of data.

Table 1. Quality and frequency of contributions to discussions over a 3-month period

A balance of qualitative (group interviews and lesson observations) and quantitative data (percentage of quality contributions in Harkness discussions) would I believed, prove that regular teaching and reinforcing of oracy skills could have a positive impact on the quality of contributions students made.

The Harkness data showed fluctuations in both the numbers of contributions (NC) and quality contributions (NQC). This is in turn affected the percentage of quality contributions week to week, depending on the topic of discussion. Significantly, the quantitative data (Table 1) reveals no clear pattern of progress. For example, one student could have 100% NQC one week and 33% the next.

What seems clear however, is in some cases the nature of the question itself affects the NC. Discussion topics that were more personal, such as friendships or personal goals and achievements, seemed to limit the overall NCs. Perhaps students felt they could not ‘open up’ or engage as much as other hypothetical questions such as superpowers, money or chocolate.

The Harkness data also reflected the challenges of the two EAL students who usually, and unsurprisingly, made fewer contributions than the other students. As their confidence increased week-to-week, so very gradually did their percentage of NQC.

However, the end-of-intervention group interview revealed a marked improvement from the first – it was clear their physical oracy skills had developed as they displayed good posture and eye contact, voice projection and gesture. They were confident in challenging each other and showed much better turn-taking skills and building on the views of others. We discussed how the intervention has impacted their confidence in class. One student said, “I am not just sitting there thinking about what I am about to say. It’s important to listen to others so you can build on it or challenge.” One of the EAL students said, “It helped… to have a start sentence like, ‘I agree because’ or ‘I disagree because.’”

In addition, it is encouraging to see a positive impact in the group room. This was also reinforced by lesson observations after the intervention in the students’ classrooms.

Research Ethics

At the start of the intervention, before the group interview, I made it clear to the students what my project was about and my role in school as Oracy Leader. I explained how I would be collecting data and that their names would be anonymous. I emphasised they were helping me and, in that way, helping other children across school. I also stressed that if they weren’t comfortable with anything at any stage of the process for any reason, then it would be fine to withdraw from the 12-week intervention. Names were anonymised for the Harkness data.

Evaluation

Various challenges emerged as the project started. For example, a small group discussion in a quiet room is distinctly different to normal classroom, where there is not the luxury of 30 minutes to talk about open-ended hypothetical questions. This therefore affects the validity of translating any findings from group to class.

I am also mindful also that this project is nestled in the wider context of our whole school oracy development. The six students in my group would be exposed to everything else going on around school to raise the status of oracy in our school community – talking assemblies, parent workshops, oracy display board, weekly Achievement Assembly oracy certificates, and so on. This is important to consider as any progress in oracy skills of the students in my target group cannot be attributed purely to their involvement in the 12-week intervention alone.

However, leading an oracy-focused discussion group was extremely beneficial to my own professional journey, especially building my confidence in subject knowledge for oracy across the school.

Another challenge was the language barriers facing the two EAL students. They needed more support than others, and it affected the flow of the group discussion. However, the group represented the diverse population of the school and meant the group was a microcosm of the wide-ranging needs of students at the school.

Analysing the Harkness data, in future I would prepare the type of topic questions more carefully as well as considering letting them emerge organically from the speaking and listening from the children themselves.

Moving forward, I will share my findings and research summary with staff to raise the profile and value of oracy across the school, in addition to supporting parents to understand the value oracy has on students’ academic future and their well-being.

References

Wilkinson, A. (1965)The Concept of Oracy, University of Bimingham

Alexander, R. J. (2013) Improving Oracy and Classroom Talk: achievements and challenges, Primary First, pp.22-29, University of York

Dockell, J. E. and Connelly, V. (2009) The Impact of Oral Language Skills on the Production of Written Text, Teaching and Learning Writing, 45-62, BJEP Monograph Series II, 6, The British Psychological Society.

Hewitt, R. and Inghilleri, M. (1993) Oracy in the Classroom: Policy, Pedagogy and Group Oral Work, Anthropology and Education Quarterly 24(4):308-317, American Anthropological Association